Nadine Kohn-Fiszel

Artiste plasticienne

SOCKS

Two major exhibitions took place in 2012, in Beijing and then in Guangzhou.

Both included around thirty paintings from the Schmates series and a monumental 25m installation, specially created for the Croisements Festival.

Punctuation marks, and more specifically the question mark and the parenthesis, were the guiding motifs. These marks, common to both languages, and the sound "Ma," which indicates the interrogative form in Chinese, are the starting point for a reflection on our questions.

Texts and reviews

Conférence

Installation "My river"

12 Juin 2012

"How to give form to signs? How to make them suggest a universe of different and complementary sounds and visual signs and new poetic associations.

Punctuation marks, and particularly the question mark, lead us to the sounds of the words that form questions in French and Chinese. In this work, I created symbols. New emoticons, perhaps, could be formed by the multiple arrangements of punctuation marks in the written communication of young people, particularly in China. I created punctuation marks, commas in the form of pins, and lines sometimes used for hyphens, questions, and parentheses—thus expressing doubt and asides.

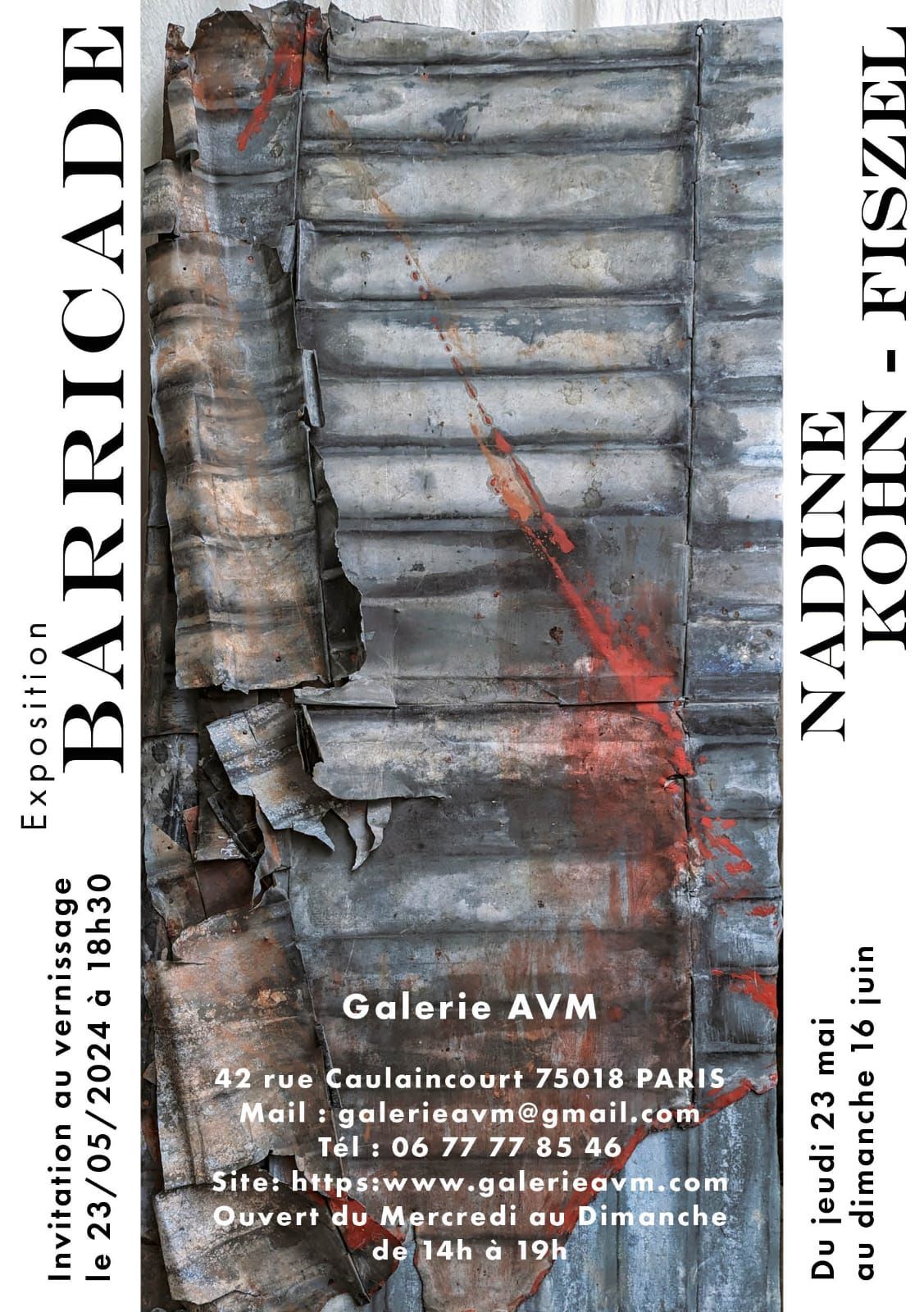

READ MORE

The parenthesis is an intermediary; it doesn't alter the meaning but provides a clue. Within this space, it opens like an oval door onto a space, here one of doubt and questioning. The parenthesis allows for discontinuity, digression without syntactic link; the parenthesis accompanies my way of thinking and my method of creation through rhizomatic growth, resonance, and rebound, and in a way, allows me to limit my explanations. In French, codified punctuation, dating back to the 8th century, facilitates the reading of texts. Writing, so interpretable until then and so difficult to segment, becomes clearer and, through the power of punctuation marks, a language, modulated by slight pauses, by stops, silences, and gaps that give birth to breath. This void, so necessary in creation, is neither an interruption nor a lack, but, as Chinese thought advocates, an active principle generating energy. Changes in tone within the read sentence create a rhythm. Texts now allow for melodic inflections, the codification of cantillation, and declamation. The question mark, originally resembling a dot surmounted by a zigzagging line to the right, likely representing the ascending movement of the voice, was initially drawn upside down and quickly acquired its definitive form. The pitch can then rise as soon as the eye perceives the question mark at the end of the sentence, as on this staircase. The spoken interrogative form in most languages requires this rising of the sentence. In French, the inversion of the pronoun and verb signifies its presence. In Chinese, the transformation came later. The simplification of the written language began in the early 1920s and marked a profound change in Chinese society. Punctuation marks replaced "empty words." It was the pivotal interrogative particle "ma" placed at the end of the sentence that, by transforming a statement into a question without changing the word order, particularly addressed me. I therefore replaced the interrogative form of my inquiries with a symbol that has become obligatory in French, immense here and placed in parentheses. It punctuates the now visible form of my doubts and uncertainties, and forms another figure of speech, an oxymoron, an ephemeral installation. For if "installer" means "to settle," it is, on the contrary, thanks to the back-and-forth between several cultures that the questioning persists and takes root. The installation establishes an interactive happening. A moment of shared writing, preserved by the video image that captures a moment of calligraphic writing on an ephemeral scroll, which can be covered over like a palimpsest if I don't ink the water with which you can deposit your quotations, your questions, your observations. The materiality of the supports and substrates is extremely important to me; they trigger my imagination and constitute my thought processes. For this installation, I returned to certain essential elements of my basic artistic vocabulary. The number of materials is deliberately reduced to give greater visibility to the ink, water, and pigments. Zinc represents the memory of passing time and the elements; felt and non-woven fabric, the memory of dwellings, their transhumance, and of clothing; thread and wire serve as a guiding thread. The metal, the zinc that forms my punctuation marks, is a flexible material for covering and enveloping, like a cloak. It retains the regular traces of its contact with the framework, its sheathing, which it conforms to and upon which the zinc plates rest. The marks of the wood's dry sap gradually settle, like imprints on its hidden face of subtle layers of lacquer, while on the other, exposed side, it absorbs the colors of the skies it observes, forming whitish streaks that characterize and protect it. Used extensively since Baron Haussmann's renovations of Paris for its ease of use, it gives its identity to Parisian rooftops. Zinc has become a symbol of Paris, constitutive of its architectural memory. I used the zinc from the old roof of my studio. Kept in my storage for ten years, I sparingly used a few patinated pieces for tentative and sometimes engraved designs, without daring to hope for such a use. I assembled the thin sheets by interlocking their edges, as the aged material resists any welding, then I cut around the edges with a blowtorch and rounded the shapes with the resulting charred borders. The seven main sections of the question mark are not all joined, and these fractures are significant. They follow the topography of the site, allowing space to flow and, partially, revealing the illegible writing of the long, painted felt strips. The cut-out pieces become scales, strange carapaces partially covered with illegible red writing, like an imaginary bone-scale script. The dots are made from thin strips cut from old sheets. Felt is a very ancient material obtained by fulling fibers and hair of all kinds, especially wool. It absorbs moisture, making it extremely durable. It is therefore a non-woven textile. Initially used by nomadic tribes for its great resistance, it is now found everywhere, especially in countries subject to wind and cold. It absorbs ink and water. It is thus used by calligraphers, bearing the faded imprint of their written signs and tracing the outline of their thoughts. For me, it is the material that symbolizes both loss and retention. Needless to say, it reacts violently to pigments. It is easily molded but difficult to paint because water and oil spread, indifferent to the hand's touch. For the past three years, I have been composing my paths and landscapes (which I call my "graphiterres") using graphite powder, zinc pigment, pencil, pastels, and sometimes acrylics. The screen and the steps are covered with it. The screen usually serves as a threshold behind which one can hide from view. Paradoxically, I invite you to walk around it, to stroll along its panels, to lift its felt veils. The folds of the fabrics or canvases on which I work are the marks of time and sometimes small, useless barriers that stop the gaze and try unsuccessfully to alter memory and the elements within their folds. The paper, also non-woven, receives your writings and the projection of their images. Pins and thread have resumed their role. Pins link work on the body and clothing, sewing and geography. They guide the gaze and delineate spaces, bounding my landscapes by mingling with lines and washes. Unlike acupuncture needles, they invite one to detach from the body and its meridians; for other journeys. I used wire extensively in the past, as a framework, or as a grid. Basic vocabulary abandoned, neglected, taken up again: rusted iron, discarded fabric, mended sheets, scorned. Materials become substance for thinking about the future: my guiding threads. Then come my writings; often formless letters, reinvented letters, forgotten languages, writings mixed together like an unconscious Esperanto. The colors used here are those I use most frequently and those I associate with China: blacks, reds, whites—the black of ink, the white of the page, of the silence of loss—and grays, all the shimmering grays, deep, light, dense, thick, intense. Each one a world, a flow. Conclusion—Some will see a back in the paintings I present around this installation. An phallic, headless, and asexual back standing on the threshold, hesitating between the present, the future, and the past, sometimes evoking the “Angelus Novus” painted by Paul Klee and described by Walter Benjamin: a body irresistibly pushing toward the future to which it turns its back, while debris piles up before it. The markings I traced on the felt of the screen and the floor are, however, the lines of a path. An intimate, individual path, with multiple ramifications that we must explore, connected to others, to the natural elements, to the world's civilizations that bring us the richness of their thought, their unique history, and with which we can build, day by day, our shared future. --For this installation, created for the Croisements festival, I attempted to weave an interwoven network of images, meanings, and sounds. The Chinese sound MA, which translates one of the possible forms of questioning, transported me momentarily to other shores, like that of Japanese space-time or the Hebrew word for "what," both pronounced "ma." The shape of the dot drew me into the fertile connections so prevalent in Chinese architecture of the circle, the square, and the rectangle. The burnt edges of the zinc envelope led me to skin, seams, and clothing. The rolls of paper took me toward the wave, writing toward the river. Each person will be able to see their own intertwinings, but which ones?

Critical

in English

Victor Wong, curator of the exhibition

The first time I met Ms. Nadine Kohn-Fiszel was during Art Canton 2010, among those art works shown in the Art Fair, not like the other artists who tried to express their emotions and concepts, attempting to display their inner world as much as they could, Nadine wanted to let go whatever left in the past, or existed at the present, or will come in the future. There was a force which contained within her works and dissolved everything in front. “Tombant noir au grillage” is one of my favorite paintings, the composition and perspective of the painting have an invisible power to attract the attentions and grasp the viewer into the “black hole” of memory. The door to the unknown world arouses the curiosity, at the meantime brings the fear to the surface of consciousness.

READ MORE

But the iron mesh forges a blockage, symbolizing a memory unbearable to recall, a spiritual struggle, and a painful breath, but everything will be washed away as time goes by. Nadine uses a way of “lightness” to handle the “heaviness” of heart and memory, she guides you to explore far into the depth of memory, meanwhile obstructs the “entry” and “information embedding”. The tableau she presents in a western way has surprisingly the similarity with the one of Chinese ink and wash drawing. Every time when I see the painting, I can’t help holding my breath, the desire of peeking the secrets of soul is increased, but restrained by another kind of power at the same time. The tension puts the viewer in dilemma, and drives him or her to explore more about human nature. It’s as if you were going through a meditation every time when you gaze at the painting. The art work reflects a kind of loneliness and coldness as well as a sense of historical heaviness, moreover, it always give you a feeling of nihility. As Genesis of Bible says: in the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth with “word”, but Nadine dissolves what He created with her “painting”. The installation “Ma River” is surrounded by her paintings in EMG Gallery Beijing. The huge reversed question mark made of the metal zinc is placed on the ascending steps in the center of the art space. On the top step there is a big dot which is part of the question mark, symbolizing the origin of everything in the world. In Chinese, the word “ma” is put at the end of the sentence, thus becomes an interrogative sentence. And the sound “ma” is the first incantation (dharani). “The earth was without form, and void; and darkness was on the face of the deep. And the spirit of God was hovering over the face of the waters. Then God said, “let there be light”; and there was light”. God created the world with “word”, and the “word” is the sound made out of God. The installation draws the viewer back to the beginning (the origin), and confronts him or her with a big question mark “why”. On the other hand, the reversed question mark suggests that the earth is only the shadow of heaven, and what we see with our eyes are only the reflection on the surface of water. The “ human backs” in the paintings around the installation stand in the threshold, hesitating between past, present and future, but all the forces come from the origin, the source, and the question mark, everything is connected, and all those paintings become the extension of the installation. What is to be is decided by what it was originally. The installation generates a great power at the centre like a spring of water, and the spring becomes a river, and the river flows into the sea… “I am the way, the truth, and the life, no one comes to the Father except through me”, here “me” stands for “ma” – the question mark ”?”…

Article

In Chinese

July 2012

Press article concerning the two major exhibitions in China, July 28, 2012. More than 50 media outlets reported on these 2 exhibitions, including newspapers, magazines, and online articles.

Press kit

Exposure The Adornment & the Imprint

AVM Gallery, Paris

EXHIBITION "ADORNMENT AND IMPRINT" AVM GALLERY

From October 7th to November 2nd, the AVM gallery presents the exhibition "Adornment and Imprint," which juxtaposes works by Nadine Kohn-Fiszel and Alain Delpech. "Adornment and Imprint" because the exhibition aims to illuminate the point of convergence between what each artist has developed in their respective artistic quests. This is an essential strategy made possible by the artist's symbolic gesture: to observe, confront, and transcend physical disappearance. From the carcasses of turtles washed up on a Gambian beach, which Delpech adorns with the full power of his imagination through engraving, to the "lost bodies" whose imprint Nadine Kohn-Fiszel recreates, everything finds its place in our world, to challenge us; everything in this rediscovered intimacy is destined for rebirth.

READ MORE

Engraver, painter, and sculptor Alain Delpech has been represented by the gallery for many years, which has dedicated several solo exhibitions to him. For Nadine Kohn-Fiszel, a painter and sculptor who lives and works in Paris and whose works have already been the subject of numerous exhibitions both in France and abroad, this is her first presentation at the gallery.

Videos

Vidéo

Installation Ma river

Pékin, mai 2012